As you know, I’ve been sharing the backstories of the various series I’ve written over the past three-plus decades. In December, I wrote about the China Bayles series (1992-present) and in January, about the Robin Paige Victorian/Edwardian mysteries (1994-2006) that Bill and I created and worked on together.

This month, I planned to write about the Cottage Tales series (2004-2011). But since some of us will be discussing Someone Always Nearby later this week, I thought I’d leave the mystery fiction for later.

Instead, I want to tell you about the Hidden Women series, which opened in 2012 with the publication of A Wilder Rose, a novel about the daughter who turned her mother’s childhood stories into eight unforgettable books—the Little House books.

Except that I didn’t start out with the intention of writing a series, and I wasn’t thinking about “hidden women.” I was thinking about Rose Wilder Lane, a remarkable woman whose work on her mother’s childhood stories has been obscured by the outsized shadow of Laura Ingalls Wilder—a figure that Rose created and nurtured, to the extent that the books she worked on under her mother’s name are far better known than her own work.

I’d been obsessed with the Wilders for decades. I’ve written extensively about this elsewhere (Writing a Woman’s Life I, Writing a Woman’s Life II, Writing a Woman’s Life III) so I won’t repeat it here. Enough to say that I dragged my husband to visit the Wilders’ Missouri farm several times and to the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library in Iowa, where I found and copied the detailed and quite incredible diary that Rose kept during the 1930s.

Finally, in 2010, I made myself sit down and start writing. I wanted to tell the true story in the same way Rose had told her mother’s true stories, so I didn’t attempt to write a biography. Instead, the book is biographical fiction: the true story of a real life, written as a novel, but always with an eye on the known, discoverable facts, so that the story corresponds to the events and significance of the life.

A Wilder Rose was finished in 2011 and I expected that a publisher would snap it up. After all, who doesn’t know about Laura Ingalls Wilder? But the story I had to tell was not the accepted “Laura” story. What’s more, biographical fiction then wasn’t the Big New Thing it is now, and some of the nearly 30 rejections were based on editorial uncertainty about this weird both/and form.

This was about the time that new technologies made author-publishing more viable, so that’s what I did. I published the book myself in 2012, then sold the reprint rights to Lake Union Publishing, which brought out a second edition in 2014. To date, the book has sold over 85,000 copies and I still hear from readers who want to know more about Rose’s story.

In those years (2012-2016), I was still writing a Pecan Springs mystery and a Darling Dahlias mystery every year, so it was a little while before I could make time for another biographical fiction project. But I already had a woman in mind: Lorena Hickok—Hick, the “intimate friend” of Eleanor Roosevelt.

I ran across Hick in the late 1990s, when I read a very bad biography and felt compelled to tell the real story. I started with the over 3000 letters the women exchanged during their 30-year friendship. Hick was one of the first female AP journalist to be assigned to “hard-news” stories (political, financial, crime), and Eleanor (with Hick’s help and encouragement) became a prolific writer. So there was a lot of material to work through, both at the FDR Presidential Library and online, in newspaper archives. But by late 2015, I had a manuscript.

By this time, I was ready to commit myself to independent publishing. I created my own imprint: Persevero Press. Persevero, Latin for I persist, in honor of the women I was writing about—women who never give up. (This was before Mitch McConnell’s 2017 “Nevertheless, she persisted” that we gleefully turned into T-shirts. Remember?)

Loving Eleanor (February, 2016) was my first Persevero Press book. In this biographical novel, Hick willingly yields her hard-earned place as a leading journalist to step into the gigantic shadow of the woman she helped to create. By the time I finished writing, I had begun to understand what Rose and Hick had in common. I also understood that those two novels were related, that I was working on a series. And I had come to realize that there are many other hidden women out there, and many, many more true stories.

The next project—The General’s Women was about two women, a wife and a lover, both hidden in the shadow of one man, a famous general and president. Kay Summersby was never recognized for what she was to Dwight Eisenhower. After the war, his staff and family did a masterful job of airbrushing her out of the picture.

But Kay was a brave woman who supported a burdened man during a tumultuous time and her story deserved to be told. I didn’t know as much about WW2 as I needed to know to write the book, so I spent months reading military and political history, studying the diaries of Eisenhower’s aides, and digging into Kay’s postwar life and death via newspaper archives. And there was Mamie, as well—basking in her hero-husband’s reflected glory and understandably jealous of the other woman in his life. The General’s Women (March, 2017) became the third book in the Hidden Women series.

There is a seven-year gap between Kay’s book and Someone Always Nearby. I was doing all my own publishing in those years, and focusing on the mysteries: A Plain Vanilla Murder and Hemlock, as well as four books in the Dahlias series and a pair of novella trilogies set in Pecan Springs.

But I continued to think about hidden women. I wanted to work on Georgia O’Keeffe, but I was hesitant, for a variety of fairly cowardly reasons. And then, once I finally summoned the courage to start working on it, I injured my spine, seriously curtailing travel. And not long after that, COVID forced us all to rethink the way we lead our lives.

I was lucky, though, to team up with the intrepid Paula Yost—a story that demonstrates what a pair of old broads can accomplish when they want to get something done. Paula and I have worked on several other publishing projects. We are fangirls of Bette Davis, who famously said “If you want a thing done well, get a couple of old broads to do it.”

So together, we read and discussed every one of the 700-plus letters that Maria Chabot and Georgia O’Keeffe exchanged, as well as the major biographies. That done, we began working our way through the archival holdings in the Maria Chabot papers in the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Archives in Santa Fe, a very fine, professionally administered repository. And when the Archives reopened after the pandemic, Paula was there to do the necessary on-site research. She is the “hidden woman” who helped me get Someone out of my head and my heart and into the pages of a book. And who helped produce the massive Reader’s Guide that you can download, free, from the Someone website.

Maria Chabot, of course, is the “hidden woman” whose loyalty, persistence, and patience create the environment within which Georgia O’Keeffe did some of her very best work, at a difficult time and in an inspiring but unforgiving desert. It was Maria who managed to keep things going at Ghost Ranch during the war and who spent five difficult postwar years designing and building the artist’s Abiquiu house. She was the someone O’Keeffe needed to give her the time, the space, and the support to do her best work—and whose abiding friendship O’Keeffe (who thought of her as a “slave”) could never quite acknowledge or appreciate.

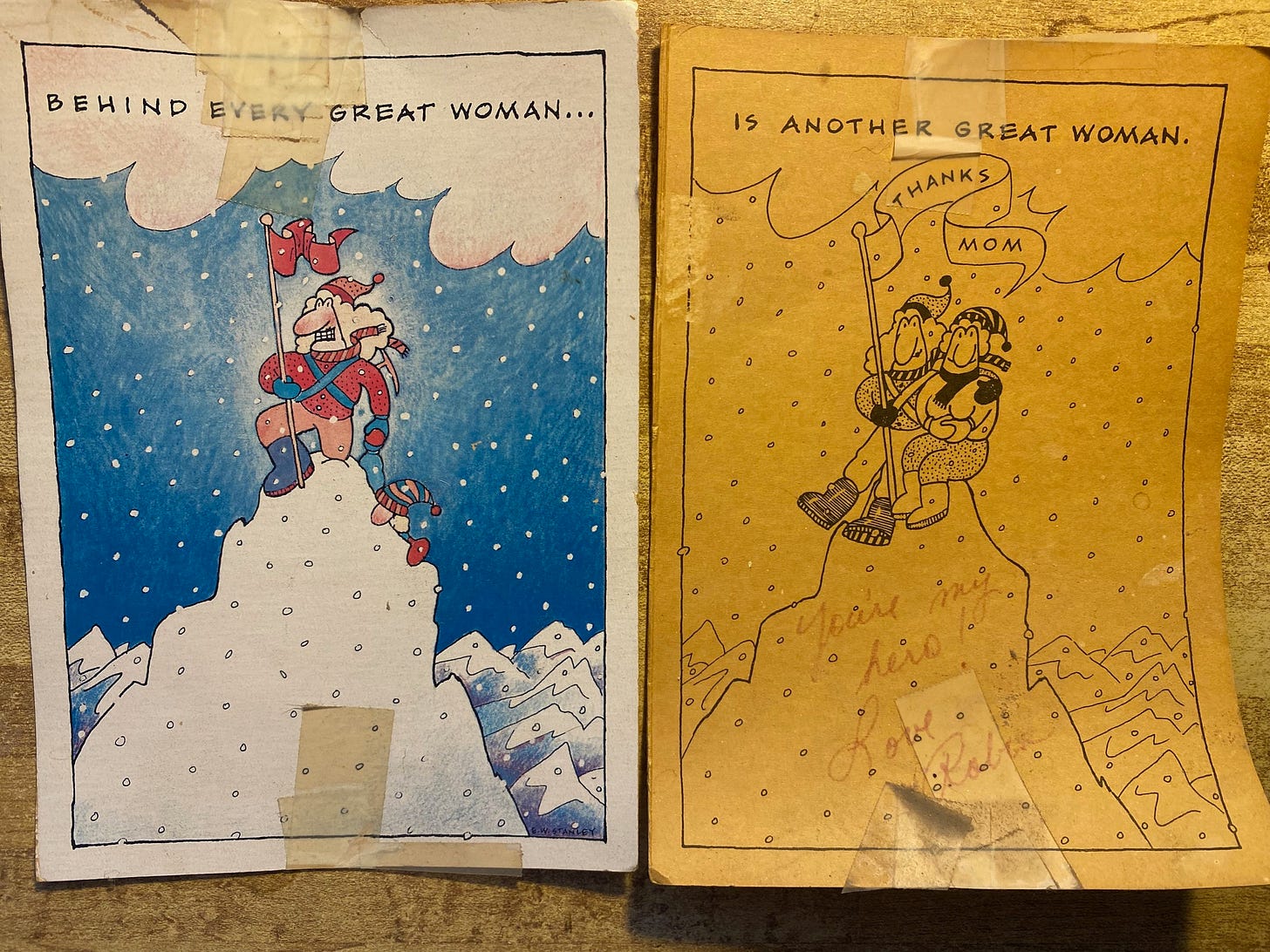

Decades ago, my wonderful daughter Robin gave me a card that I taped above my computer where I see it every day. It’s tattered now and faded, but it illustrates an important truth. There are two great women on that card, and when they’ve reached the top, one isn’t hidden behind the other. They are side by side, together.

Beside every great woman is another great woman.

And beside the two of them, unseen, there are more. Dozens of women, clans and tribes of women, past and present, real and virtual, all part of the support team. Every one of these women has a story.

Your turn.

Do you know of a book about a hidden woman that you would recommend? For instance, one of my favorites is Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA, by Brenda Maddox, about the woman whose scientific work was hidden in the shadows of the three men who walked away with the 1962 Nobel Prize for Medicine. Or maybe you’re thinking of a hidden woman who should be remembered in a book. Your comments and contributions are always welcome!

To Sue Kusch: Many thanks for letting me know that the comments were off! On now, with apologies to all who tried to comment earlier.

I read this post, and every comment. I’d love to see some of the women suggested “taken on” as fodder for your wonderfully agile pen! Rather selfishly I thought of my mother! Born in 1914, first child and only daughter and a PK, she graduated from college in 1938 with a degree in business administration. She never held a job in her field. She met my father in the business admin courses. They were married in 1938 upon graduation. The rest, they say, was (NOT) history! How many thousands of other women walked in my mother’s steps? Well educated, highly intelligent, deeply committed to politics and women’s rights? Hmmm.