In the first post in this series, I wrote about why I chose to begin doing research into the life of Rose Wilder Lane. Here’s Part 2.

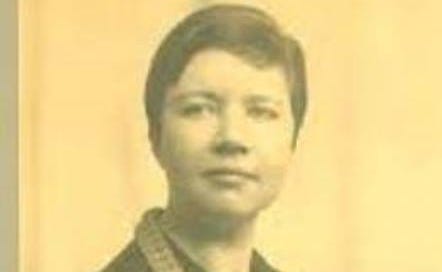

When I first learned about Rose, back in the early 1970s, I had no idea that, years later, I would write a novel about her—I was simply curious about her. I had discovered from the introduction of The First Four Years that Laura Ingalls Wilder had a daughter, Rose, and that—even though her writing career had long been overshadowed by her mother’s— Rose was remembered at least by some as a “famous author” who traveled abroad and wrote a “number of fascinating books.”

This intrigued me, and I began to collect Rose’s writings, discovering that she was an accomplished and impressive professional writer with a long string of newspaper stories, feature pieces, travel articles, books, and magazine fiction to her credit. I also compiled a timeline of Rose’s life, beginning with her birth in 1888 on the Wilders’ claim in Dakota Territory, through t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thyme, Place & Story to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.